Nevada’s “Lost City,” located northeast of Las Vegas on a terrace above the Muddy River, has been lost twice before – first abandoned by the native people who built it, then later flooded beneath the waters of Lake Mead – but a team of archaeologists from the Desert Research Institute’s Las Vegas campus hopes to ensure that it isn’t lost a third time.

This summer, DRI researchers JD Lancaster, Tatianna Menocal, and Megan Stueve plan to use unmanned aircraft system (UAS) or drone technology to create high-resolution 3-D maps of the Lost City archaeological site, which consists of about 46 adobe structures that date back more than 1,000 years. Working with representatives from the National Park Service, the team will then use these detailed maps of the structures and topography to devise best management practices for the continued preservation of the site.

“The structures are set on old river terraces and lake deposits that are really susceptible to erosion, and as the level of Lake Mead has dropped, the erosion seems to have accelerated quite a bit,” said Lancaster, Assistant Research Scientist of Archaeology at DRI. “Our goal with this project is to try to figure out where erosion is particularly bad and to try some different techniques to help control that erosion.”

Lost in time

Lost City, also known as the Pueblo Grande de Nevada, was home to a small community of people of the Puebloan culture from about 800 A.D. to 1300 A.D. Here, they lived along the banks of the Muddy River, farming crops such as corn, squash, cotton and beans, and supplementing agriculture with wild and hunted foods.

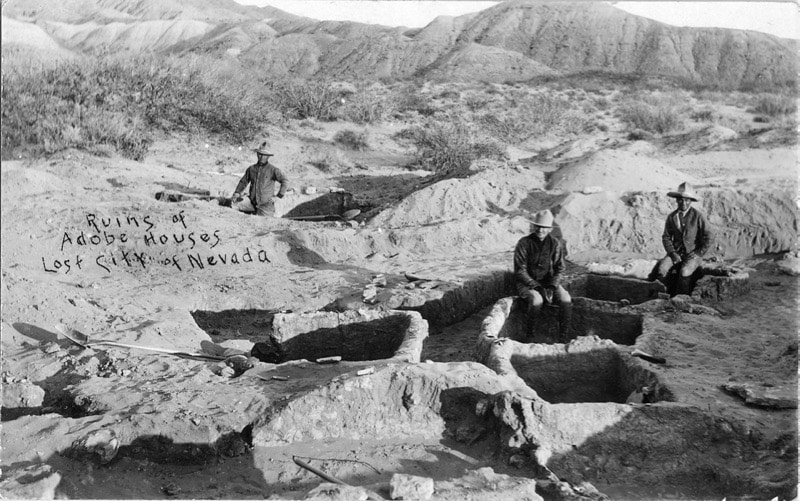

No one knows exactly why Lost City was abandoned by its original inhabitants, but once the remains were discovered in the 1920s, they were mapped by archaeologists. After the construction of the Hoover Dam in 1935, the rising shoreline of Lake Mead became a threat the site.

“The area was inundated by the rising waters of Lake Mead after the construction of the Hoover Dam. Original researchers and the Civilian Conservation Corps were under a time crunch to get all the data they could while the Dam was being constructed, all the while knowing it would be lost after inundation,” said Stueve, Staff Research Scientist of Archaeology. “Fortunately, only half the site was inundated by high water levels and as the water receded from years of drought, the site was fully exposed once again and available to study.”

The ruins were studied again in more detail in 1979 through the 1990s, by which time extensive erosion had already damaged a number of the structures.

“One thing that has always been noted in the archaeological studies is the level of erosion in this area,” said Menocal, Assistant Research Scientist of Archaeology. “Entire landforms or portions of the landforms have been eroded away, so portions of the site are no longer there. In some places, entire houses are gone.”

Today, Lost City is listed in the National Register of Historic Places and managed by the National Park Service as part of Lake Mead National Recreation Area. Lancaster, Menocal, and Stueve approached NPS with an idea for a partnership to aid in preservation of the site. When an opportunity to fund the project through DRI’s Lander Endowment became available they realized the partnership was a possibility.

“We were looking for ways that we could branch out and impact the local community and the local resources around us a bit more,” Lancaster said. “We have a lot of capabilities at DRI; it’s the type of place that has the infrastructure for us to do high quality and meaningful environmental science.”

A plan for preservation

To help protect Lost City from further damage, the DRI team plans to use UAS technology to create high-resolution maps of the area, through a process called photogrammetry.

“The UAS will fly around and take a series of several hundred photos of the area of interest, and we’ll use that to essentially build a 3-D model of the surface,” Lancaster explained.

They will use the maps to identify areas where erosion has occurred in the past and present, as well as areas where they expect erosion to occur in the future. During the summer of 2020, before the monsoon season hits, the DRI team will work with representatives from NPS to design effective treatments for the erosion problem. They plan to monitor the results of their efforts using UAS photogrammetry as the monsoon season progresses.

“The erosion is focused in these deep gullies that have formed in soft sediments, and these gullies are causing damage to the site as they expand and run into each other,” Lancaster said. “So, we’re planning a paired study. We’ll install an erosion treatment in one gully, and the other gully in that pair will not get a treatment. We’re essentially testing the effectiveness of erosion treatments approved by NPS management.”

The team is still looking for funding for another component of the project, which would utilize a thermal sensor on the UAS to detect structures or stone objects that are buried beneath the land surface.

“Out at Lost City, there are probably still structures that are buried beneath sediments, that you can’t actually see,” Lancaster said. “If we could discover where they were, and discover where gullies or erosion might expose them and start to damage them in the future, we could actually prevent them from being damaged or exposed in the first place. That’s one really exciting aspect of the project that we’d love to have the opportunity to test.”

LEARN MORE

About Pueblo Grande De Nevada (Lost City), from Online Nevada: http://www.onlinenevada.org/articles/pueblo-grande-de-nevada-lost-city

About Lost City Archaeology, from Online Nevada: http://www.onlinenevada.org/articles/lost-city-archaeology

About Pueblo Grande De Nevada (Lost City) from the National Park Service: https://npgallery.nps.gov/AssetDetail/6b5182e4-c08c-4a6f-a296-e94058ebd6e1