How DRI scientists are tackling extreme heat

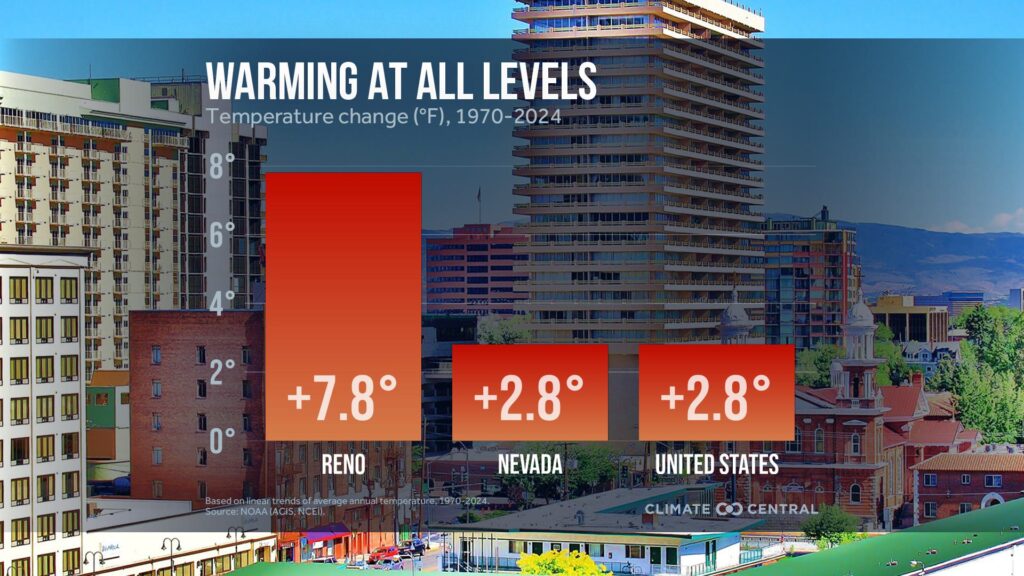

Earth is hotter than it has been in 125,000 years, scientists say, and this warming trend shows no signs of changing. Here in the U.S., Nevada – already the driest state in the country – is in the hot seat. Reno tops the list of the nation’s fastest warming cities, with Las Vegas coming in second place.

DRI scientists are concentrated at our two campuses in both cities, with their lives and communities at the epicenter of extreme heat. Many of them apply their expertise in climatology, air quality, public health, and hydrology to the topic, with dozens of studies focused on finding solutions and effective adaptations occurring at any point in time.

The Hottest, Biggest Little City

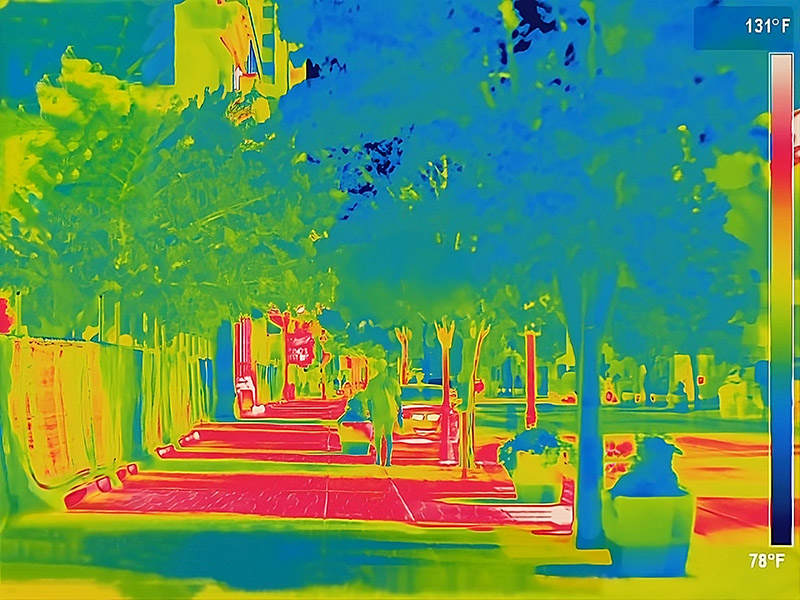

Walking around Reno, Nevada on a hot summer day can feel punishing. The sun’s rays are so strong in this high desert city that your skin instantly feels the relief of a shade tree, when you can find one. On one early July day, the afternoon air temperature measured about 98 degrees—not the hottest day for the city, but on the hotter end. Yet a thermal imaging camera that registers the surface temperature of everything within the image frame tells a different story. One downtown street near the historic Biggest Little City arch shows sidewalk temperatures of 135 degrees in the sun, while adjacent stretches shaded by trees measure 78 degrees. This dramatic heat spectrum is shown by the camera as striking contrasts of deep red and dark blue.

The information is a visual reminder of the urban heat island effect, or the way that cities absorb and retain heat in ways natural landscapes don’t. The asphalt, concrete, and metal used to build human infrastructure exacerbates the warmth of the sun’s rays, absorbing and radiating heat in uneven ways throughout cities. Research like the 2024 Reno-Sparks Heat Mapping Project captures how these heat islands are distributed and uses the information to help city planners and scientists tackle the problem. As in other cities across the world, the problem tends to be most acute in lower income communities that lack the shade of historic trees. Unfortunately, these are the same neighborhoods where many people can’t afford air conditioning.

The problem becomes more acute when wildfire smoke fills the city’s air, as is happening more frequently as wildfires grow bigger and more intense. When extreme heat coincides with unhealthy air quality, residents without central air conditioning face difficult choices. Many residents cool their homes by opening windows at night to draw in the cool night air, but this could put them at risk from the negative health impacts of smoke. Window air conditioning units and evaporative coolers may also draw in smoke from outdoors, creating hazardous air quality levels inside the home.

Kristin VanderMolen is partnering with Northern Nevada Public Health to better understand the risks. By installing air quality sensors in the homes of Reno community members and conducting health monitoring during wildfire smoke events, her research seeks to pinpoint how public health is impacted when both heat and smoke are pervasive. “We know that both extreme heat and wildfire smoke exposure come with health risks, and we’re hoping to gain clarity on how these overlapping events can exacerbate the toll on the human body,” she said.

The Nevada Heat Lab

In Las Vegas, where temperatures regularly soar above 100 degrees, escaping the heat becomes a question of survival. Clark County lost more than 500 lives to extreme heat in 2024 alone.

“People often ask me if heat will one day make Las Vegas unlivable,” said David Almanza. “And I tell them that for more than 500 people last year, it already is.”

Almanza works in DRI’s Nevada Heat Lab, a research effort that started in 2023 to bring scientific expertise to the issue of extreme heat in the state. Led by Ariel Choinard, the group brings together government agencies, nonprofits, and researchers to understand the breadth of the problem and identify opportunities for solutions.

When a heatwave hits Las Vegas, the city prepares by establishing places like public libraries as “cooling stations.” These effectively serve to offer the comfort of air conditioning to community members who lack it at home. But Choinard points out that many of these locations are closed on public holidays and few are open at night, leaving people exposed to the heat. Las Vegas nights see little relief from the heat of the day, with temperatures often remaining in the 90s—another result of the urban heat island effect.

Almanza conducted a study to better understand how cooling stations are serving the needs of community members. In the summer of 2025, he visited cooling stations throughout the Las Vegas Valley to survey their staff. One benefit that has already come from the Nevada Heat Lab’s work is that these cooling stations now offer free bottled water. The small and simple step highlights how few resources are typically dedicated to addressing heat.

“There were more than 500 heat deaths in the county last year, compared to 293 vehicular deaths,” Choinard said. “Think about how many resources we put into trying to prevent vehicular deaths compared to how little is done to prevent heat-related deaths.”

Promoting tree planting is one way the region is attempting to find relief from the desert sun. Cayenne Engel, another member of the Heat Lab, is an urban forester examining the efficacy of tree planting programs across the Las Vegas Valley. She is visiting recently planted trees to see how they’re faring, examining which species are growing most effectively, and measuring the cooling benefits they offer. She is also offering assistance to community members who have questions about how best to care for their trees.

Using advanced computer modeling techniques to create a “digital twin” of the city, John Mejia and Juan Henao found that trees can offer 30 degrees of cooling power to Las Vegas community members, simply by blocking the sun’s rays. This difference in air temperature can be a huge relief, bringing the air to a more comfortable 90 degrees Fahrenheit on summer days reaching up to 120 degrees. Unfortunately, their research also found that despite the power of their shade, trees struggle to bring the air temperature down in Las Vegas the way they can in more humid locations.

Research in other cities has shown a larger citywide air temperature decrease resulting from transpiration, or the way that trees release water vapor from leaves (the evaporative cooling process is similar to sweating in mammals). However, in the extremely dry desert air, the study found that many trees will close their stomata, essentially pores in their leaves, to conserve water; this limits their air-cooling benefits beyond shading. The finding is consistent with other research that found hot, dry areas receive 40% less evaporative cooling from trees than more temperate environments.

“Trees can really improve our thermal comfort, because when we go under a tree, we can feel the difference,” Henao said. “But this comfort is due to more than temperature — we’re also feeling the difference in the amount of solar radiation that is reaching us. I think one important finding of this research is that air temperature is not the only variable that matters.”

Mejia and Henao are using computer simulations of cities across the country to examine a range of heat mitigation measures. Each city has a unique climate and infrastructure, making it important to identify individualized solutions.

“Street trees are an important part of the solution to urban overheating,” Mejia said. “However, to equip practitioners with a more comprehensive set of tools, our ongoing research is also investigating a wider range of heat mitigation strategies, including reflective materials for rooftops, walls, and pavements; green roofs; and improved energy efficiency in buildings.”

An Atmospheric Sponge: Droughts, Floods, Then Fires

The urban heat island effect is one significant reason Nevada’s cities are warming so rapidly, as both metropolises sprawl to accommodate growing populations. But soaring temperatures are happening everywhere across the globe. Thanks to the increase in gases like carbon dioxide and methane from human activities, the atmosphere is simply holding more of the sun’s warmth than it used to.

The implications of a warmer atmosphere can be seen in news headlines every day – droughts, floods, and wildfires. For every degree Celsius it warms, the atmosphere can hold approximately 7% more water, which means it will draw this additional moisture from Earth’s rivers and plants, exacerbating droughts. Moisture-filled clouds can then release supercharged storms, causing flooding that can devastate homes and farmland. These storms can also cause bursts of plant growth, which then dries out when drought conditions return– setting the scene for intense wildfires. DRI’s Christine Albano published her research on this “hydroclimate whiplash” just as the Los Angeles wildfires were burning out of control, and followed up on the findings with a more targeted analysis of the conditions that led to the unprecedented inferno.

“My hope is that this work brings greater recognition to the fact that wet and dry extremes are linked together and that a warming climate is likely to intensify both ends of the spectrum,” Albano said. “The key takeaway is that we can’t plan for these in isolation.”

Albano teamed up with Maureen McCarthy to help communities prepare for extreme weather events. Their ArkStorm project simulates a historic storm from the winter of 1861 that flooded California and northern Nevada communities, enhancing the impacts to reflect the effects of a warmer climate. The scenario includes detailed maps of potential flooding that were provided to emergency managers in communities across the Reno/Tahoe region to help them prepare. Albano and McCarthy also produced a report that provides guidance for incorporating climate data into emergency planning and exercises. It can be used to help prepare for a range of extreme weather events, from wildfires to floods and landslides.

“This primer provides a guide for emergency planners to develop scenarios that can test their ability to anticipate, respond, and recover from these events and to inform actions for strengthening community resilience in the future,” McCarthy said.

Infinite Connections

These projects represent just a small fraction of the ways DRI scientists are striving to uncover the impacts of a warmer atmosphere. Our research truly spans the full range of environmental and human impacts, from helping the nation understand how water availability is changing on the Colorado River, to partnering with other universities to use scientific expertise to solve the Southwest’s biggest challenges. DRI scientists are at the leading edge of scientific innovation to answer the questions that matter most.

To support our work on science that matters now, consider contributing to the DRI Foundation. Your help empowers our efforts to pursue solutions to the nation’s most pressing issues.