Written by Ileah Kirchoff

The Desert Research Institute’s Native Climate education team, Ileah Kirchoff and Crystal Miller, hosted a collaborative workshop between the Walker River Paiute Tribe and the Fallon Paiute Shoshone Tribe on May 4, 2024. In attendance were Indigenous knowledge holders from Walker River Paiute Tribe, Kutzadika’a Tribe of Mono Lake, and Fallon Paiute Shoshone Tribe; elected Tribal leaders from Fallon Paiute Shoshone Tribe and Kutzadika’a Tribe of Mono Lake; and educators from Mineral County and Churchill County School Districts.

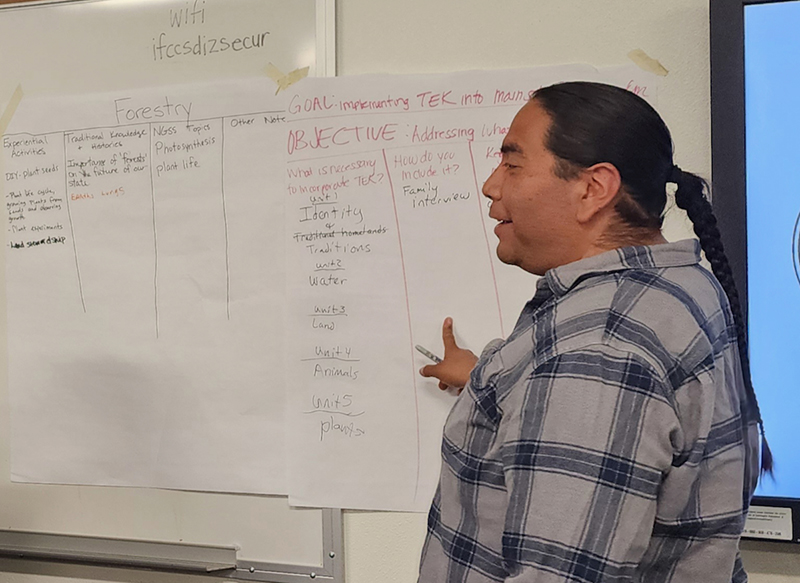

The session focused on Indigenous curriculum development and the incorporation of Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK), particularly in lessons about the climate crisis. Meaningful Indigenous curriculum requires us to take a step past culturally relevant content in order to change the paradigms through which we teach young people. Participants enjoyed sharing their knowledge, modeling learning through experience, creating educational resources, and conversing about how education can reach all students through change.

Through the workshop, knowledge holders worked collaboratively with classroom educators to develop curriculum that incorporates Indigenous and place-based education practices, particular to their own regions. These curriculum resources were created with a foundation of TEK from Tribal leaders, Indigenous knowledge holders, and Tribal members, while still following the required Next Generation Science Standards. Promoting Tribal sovereignty through education and curriculum development was a popular topic that introduced a larger view of the world from a linear science-based understanding to a cyclical one.

As the workshop progressed, participants modeled learning by interacting in hands-on learning stations and discussions surrounding the following questions:

- In what ways could this lesson promote tribal sovereignty and self-determination?

- How could this lesson include storytelling and history?

- How can this lesson emphasize students’ responsibility for the environment and the community?

- How can you promote perspectives of parents and families in a positive way?

- How can you reference modern Indigenous events and challenges?

These open-ended questions allowed conversations to flow naturally, as all individuals discussed their own experiences in education.

In break-out groups, participants brainstormed the necessary TEK components, the actionable steps, and the key role players within Indigenous curriculum development. Anti-racist work in the education system was a challenging topic that attendees worked through gracefully, listened to one another, and communicated solutions to reforming this educational issue through collective efforts and policy change.

The DRI Climate Education team plans to host follow-up workshops between the two tribes to advance the mission as well as continue to assist and foster collaboration between Tribal educators and Tribal representatives. The next meeting is tentatively scheduled for October 2024.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS:

We would like to thank Churchill County School District for providing a workshop space. We would also like to thank the following individuals, who helped with recruitment, feedback, and preparation for this event:

- Lisa Bedoy – Community Learning Center/Education Director – Fallon Paiute Shoshone Tribe

- Kathryn Bervin-Mueller – Director of Learning & Innovation – Churchill County School District

- Selena Gomez – Administrative Clerical Assistant – Churchill County School District

- Andrea Martinez – Chairman – Walker River Paiute Tribe

- Sara Twiss – Education Director – Walker River Paiute Tribe

- Lance West – Principal – Shurz Elementary School

- Cathi Williams Tuni – Chairman – Fallon Paiute Shoshone Tribe